A Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy (RARP) is the operation of choice for a man needing surgery for prostate cancer. Mr Cahill is a leading expert in this operation. More information about the operation and Mr Cahill’s outcomes can be found below:

The surgical procedure of choice for prostate removal is a Robotic-Assited Radical Prostatectomy (RARP).

The ‘robot’ is in fact just an instrument which translates the surgeon’s actions. It can only do what the surgeon does. The technology of the robot offers brilliant, well-lit vision that is magnified so the surgeon can easily see the site. The robot is extremely dextrous, so delicate surgery is possible. The surgeon sits at an operating console, looking at the screen which relays the images the robot provides. The surgeon moves their hands to dictate to the robot what to do.

These qualities improve the operation because the prostate gland sits within a man’s pelvis. Operating in this area conventionally is limited by a lack of space to manoeuvre and by difficultly in being able to see clearly.

This technology has improved outcomes for patients.

Benefits of RARP

- Better vision than any other surgery. The more you can see, the better you can do.

- The dextrous instrumentation delivers complex surgery intuitively.

- More accurate and less invasive surgery allows for faster recovery.

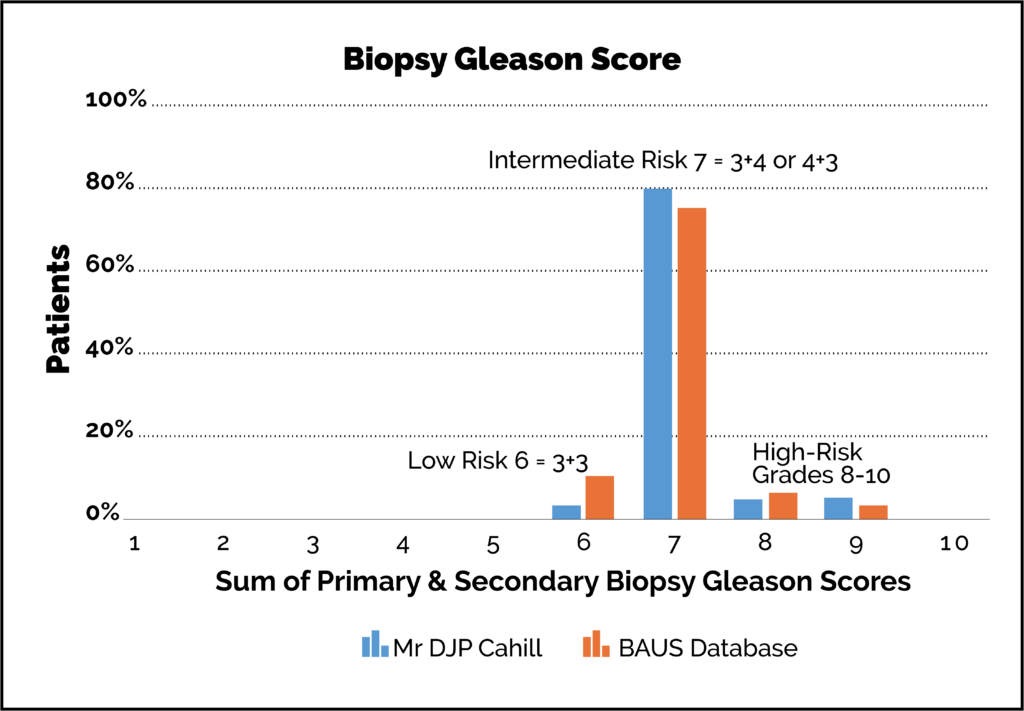

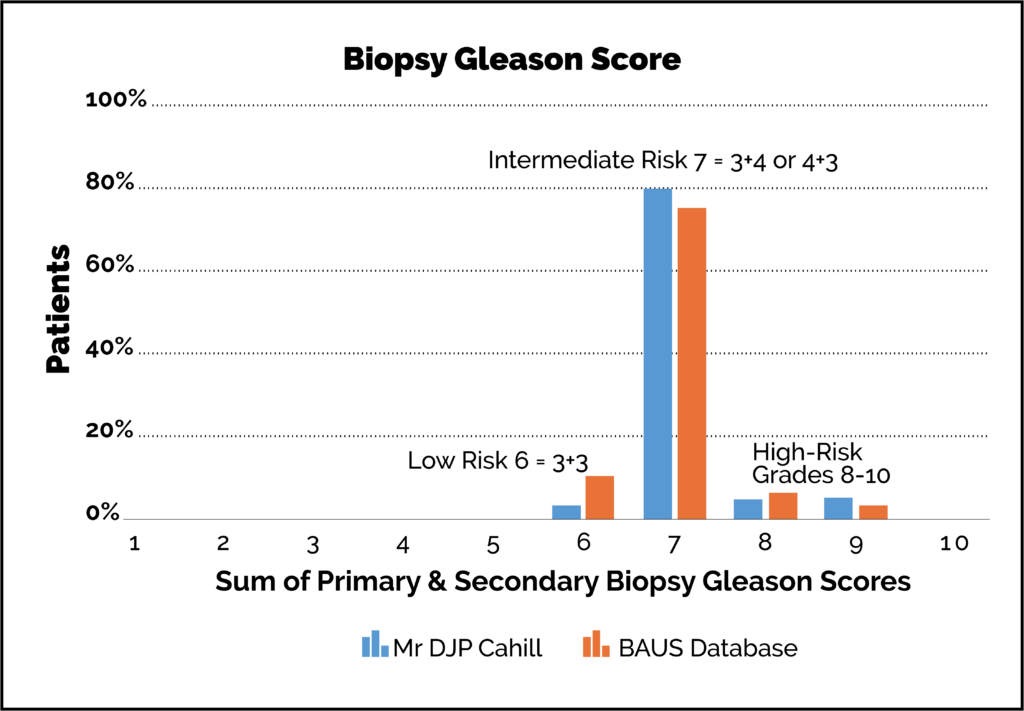

At the time of diagnosis, the grade or stage of the patient’s prostate cancer is determined. Essentially, this is a marker for how severe/extensive the cancer is and it helps to guide decision-making about management. This is known as a ‘Gleason Score’ (learn about Gleason scoring here).

Although lower-grade cancers may not need surgery per se (they can be monitored instead by Active Surveillance), we will occasionally operate for select cases of lower-grade Gleason 3+3:

- patient choice usually linked to a family history.

- MRI evidence of high-volume disease.

- diagnostic uncertainties around PSA level.

- palpable disease on examination suggesting it is more aggressive.

- certain genetic markers prompt treatment over surveillance.

Ideally the prostate cancer is removed in its entirety with the prostate. The cancer can be confined to the prostate (stage T2) or may microscopically be invading the capsule and fat that sit around the prostate (stage T3). Both stages T2 and T3 are curable. T3 disease more often requires extra treatment such as radiotherapy and drugs.

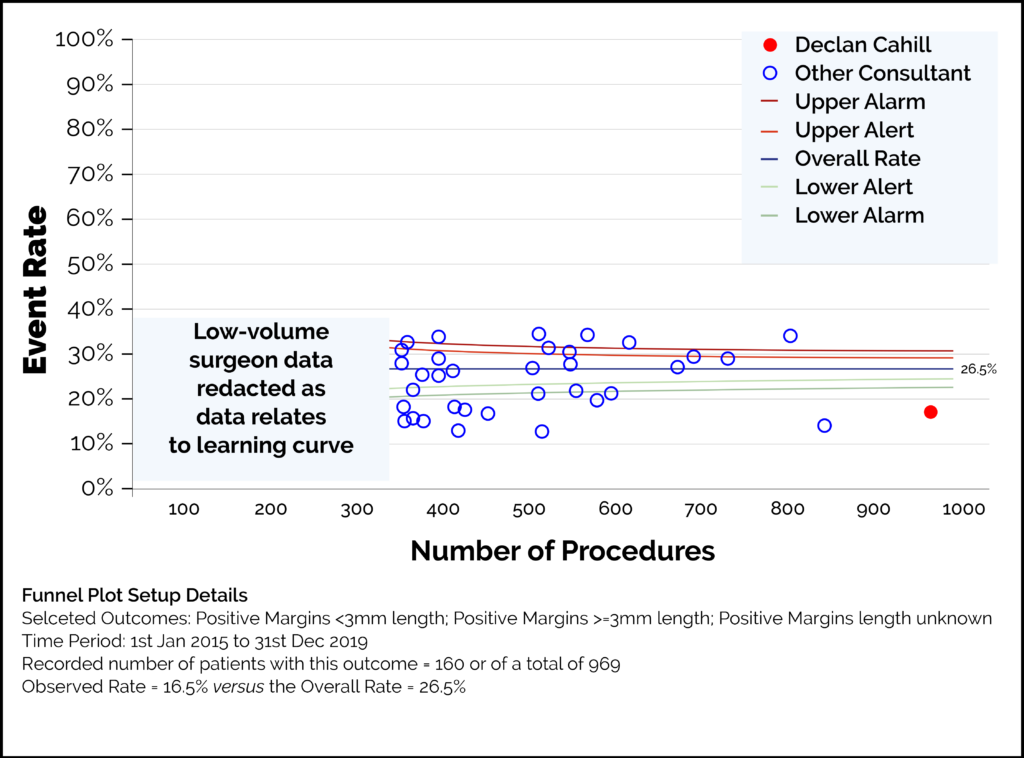

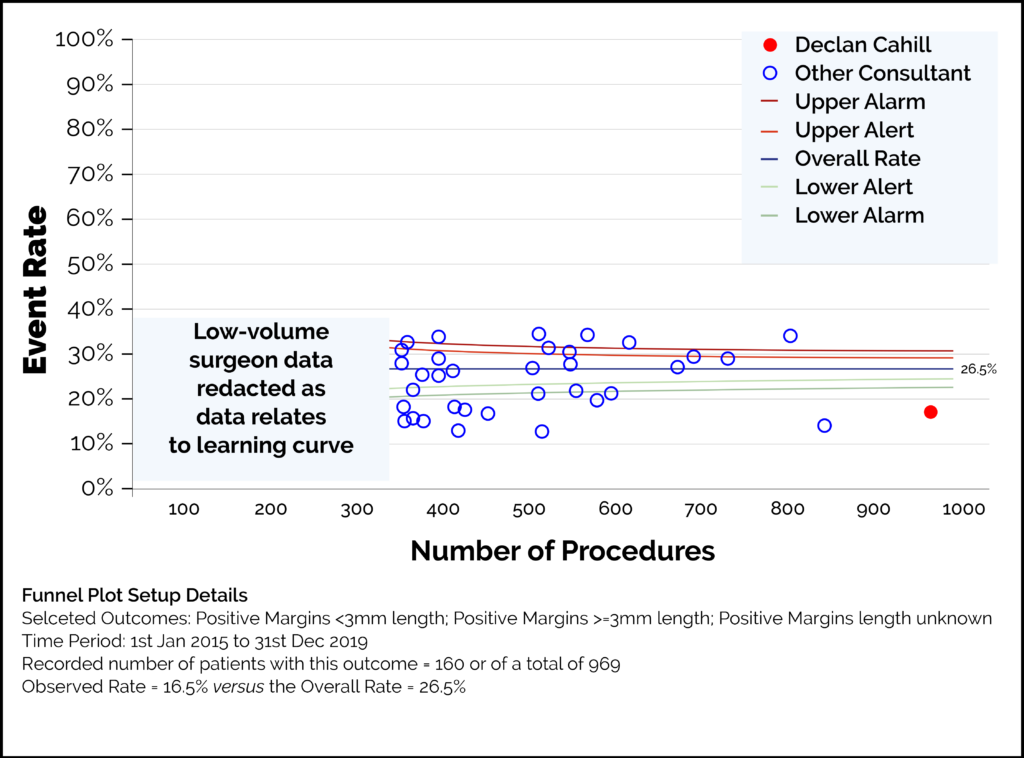

After surgery, the specimen that has been removed is sent for histological inspection by a specialist pathologist. If there is cancer seen on the edge of the specimen it is referred to as a ‘positive margin’. Positive margins are more likely with a high volume of prostate cancer in the specimen, the position of the cancer, nerve sparing surgery (see ‘erectile function’ section) technique and the techniques used to maximise continence outcome. Experience and surgical skill can be reflected in lower positive margin rates seen in a surgeon’s outcome data. Low positive margin rates can be used as a quality indicator of surgical technique.

- Declan Cahill has operated on more than 2,000 cases since 2003.

- 980 cases over the past five years since starting at The Royal Marsden in 2015.

- 5% low-risk cases, 60% intermediate risk and 35% high-risk disease (using the D’Amico classification).

- 69% of patients had one or both nerve bundles spared depending on disease risk. These nerves are spared to improve sexual function outcomes (cancer allowing).

- Overall positive margins 16.8% (see above explanation).

- 51% cases were stage T2 confined to the prostate (11.6% T2 positive margins).

- 49% of cases were T3 locally advanced (23% positive margin rate).

We looked at a group of patients since 2015. We had follow up data on 800 out of 802 patients with at least 12 months follow up and a mean of 35 months follow up.

Overall, 17% of patients will have radiotherapy added to surgery for recurrent disease at a mean of 15 months following surgery.

For low-risk cancer the risk of subsequent radiotherapy is 2%. For intermediate risk cancer it’s 13% and high-risk cancer 32%.

This means that those patients who need it get as much treatment as is required whilst those with low-risk disease get as little as possible.

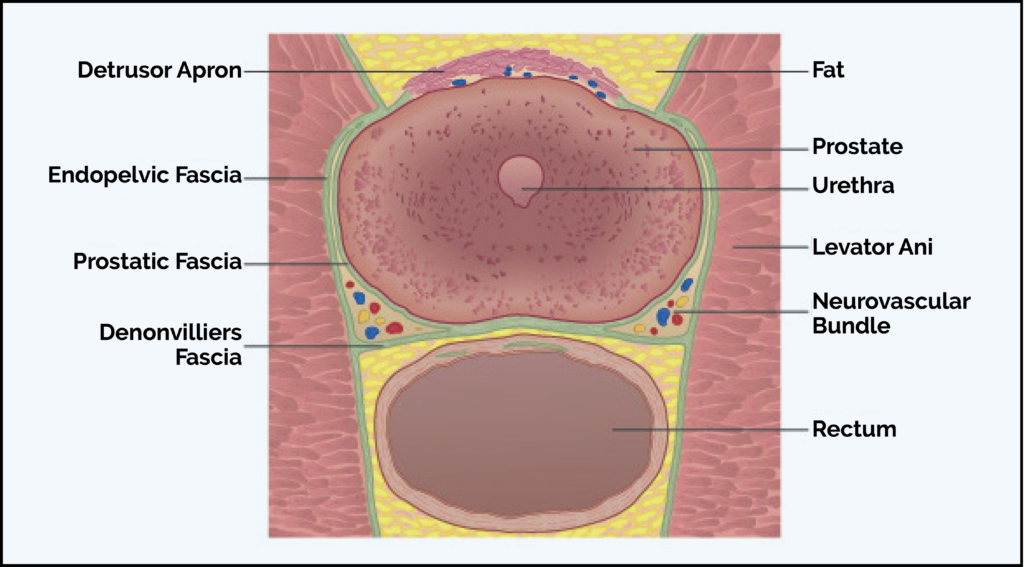

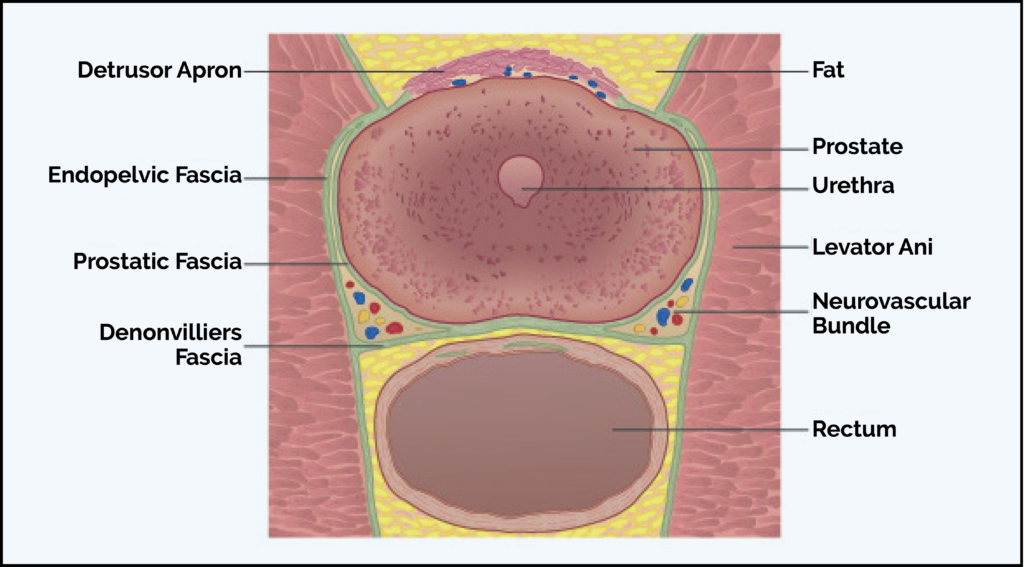

The prostate gland encircles the top of the urethra (the tube which takes urine from the bladder through the penis). Operations in this area can affect urinary continence and a fear of incontinence can be a source of anxiety for men considering surgery for their prostate cancer. Bowel continence is not affected.

By constantly reviewing the outcomes for my patients and seeking even better results, I am able now to more easily identify those patients who may be predicted to suffer from long-term incontinence post-surgery. This means I can take measures to try to avoid it during the operation or recommend a different treatment.

As a result of this research there has been no need for further surgery to correct significant incontinence in the last 500 patients operated on. Prior to that, 1% of men had distressing long-term problems with incontinence.

Identifying the significance of the membranous urethral length has been key to this improvement.

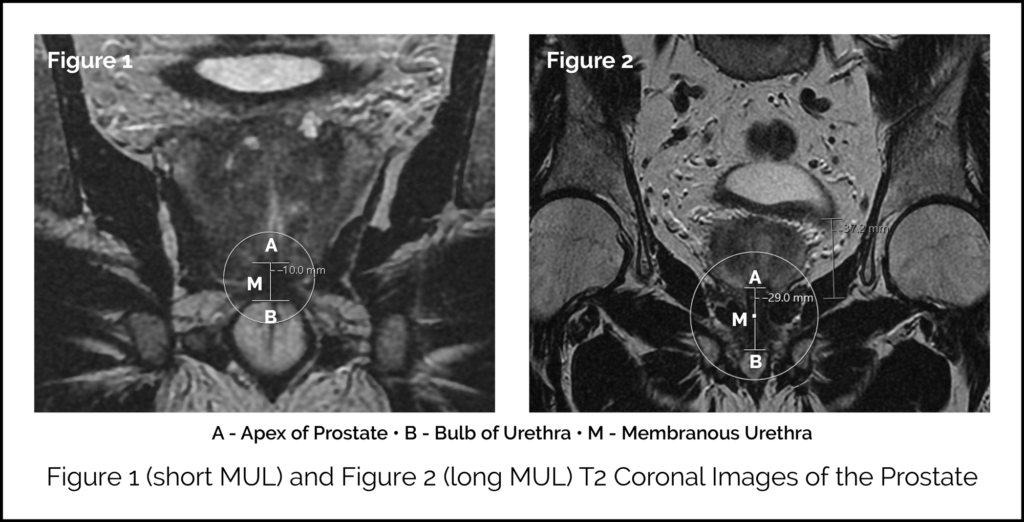

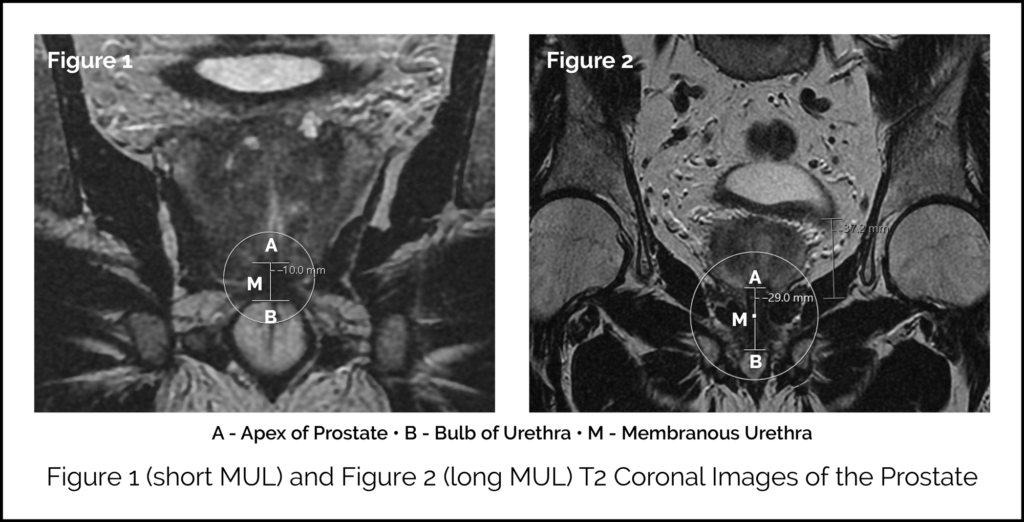

MRI scan images showing the measurement of the MUL

MRI scan images showing the measurement of the MUL

Membranous Urethral Length (MUL)

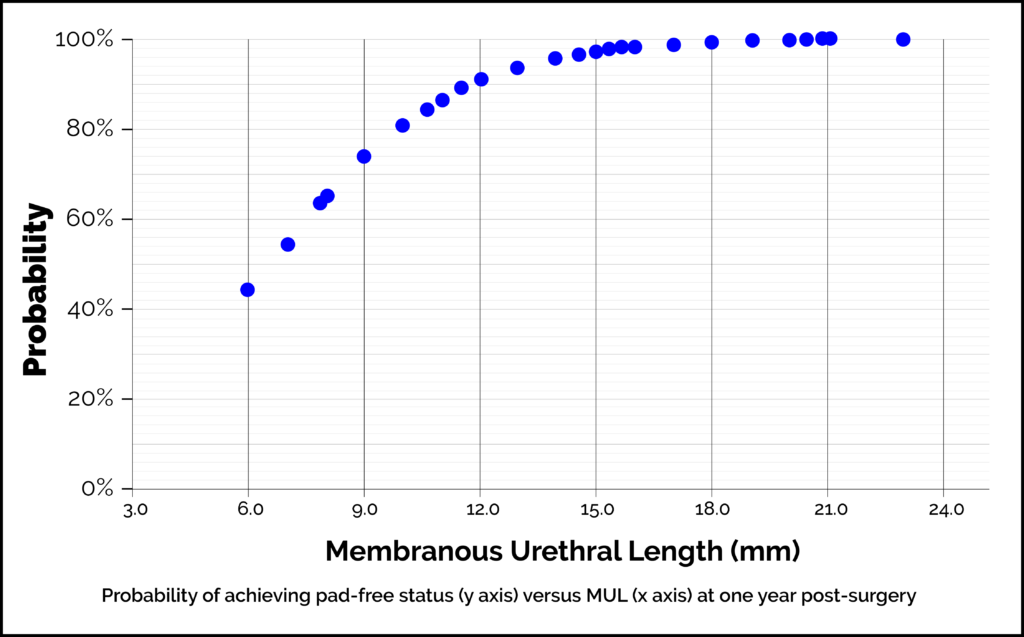

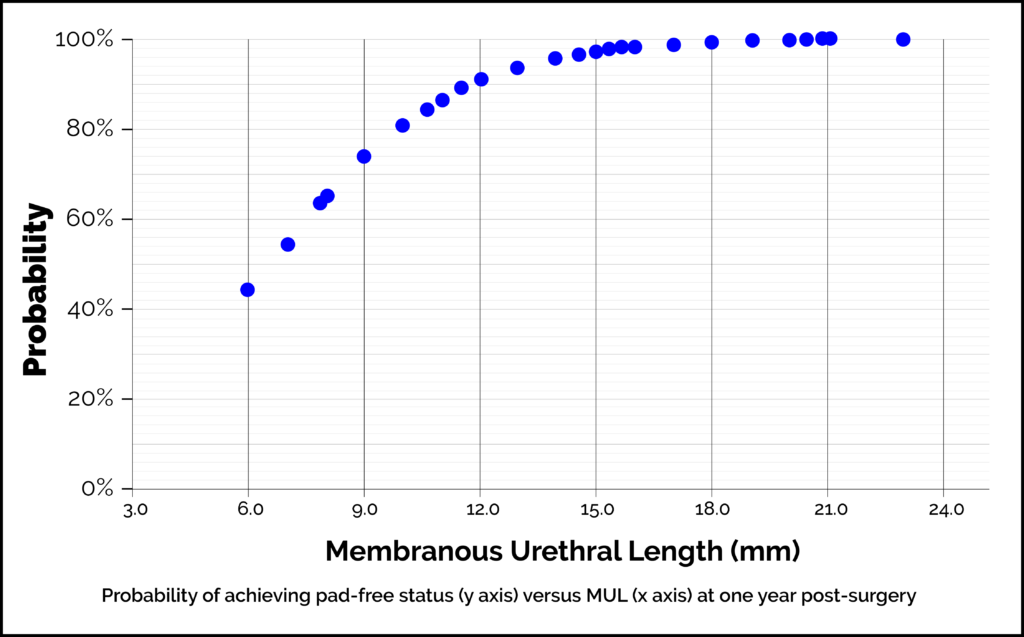

It is now apparent that differences in individual patient anatomy are important and influence outcomes to post-surgery continence. The membranous urethral length (MUL) is the length of the external urethral sphincter. This is the muscle that closes the membranous urethra and ensures the male bladder is not just a bucket with a hole but a continent reservoir which can be emptied consciously. One way to visualise this is to clench your fist over a pen (the pen acts as the urethra and the fist represents the external urethral sphincter). There is natural variation seen in men: sphincter length can vary all the way from one finger/knuckle to five. Someone with ‘one knuckle’ equivalent can hold onto dryness in normal circumstances but can’t tolerate surgery. They can be predicted to end up with difficult incontinence post operation. Someone with ‘five knuckles’ of muscle can be predicted continence in almost any scenario. A patient’s MUL can be measured from an MRI before any surgery. We measure it as the distance from the apex of the prostate to the bulb of the urethra. This is a reliable, simple and easy assessment, which can guide assessments of patient-specific risk of post-RARP incontinence. In our study the mean MUL was 14.6mm. The risk of incontinence was 27% if the MUL was <10mm and 2.5% if >15mm. The risk was age-dependent too. Only 3% of patients have a MUL <10mm. 98% of patients with measurements above the average will do well. We can offer specific types of surgery for those with measurements below average when the type of cancer you have suggests surgery is the optimal course of action. The graph below shows how the length of your urethral sphincter muscle affects the probability that you will be ‘pad free’ (ie continent) at one year after surgery. MRI scan images showing the measurement of the MUL

MRI scan images showing the measurement of the MUL

Adaptations to Surgical Approach

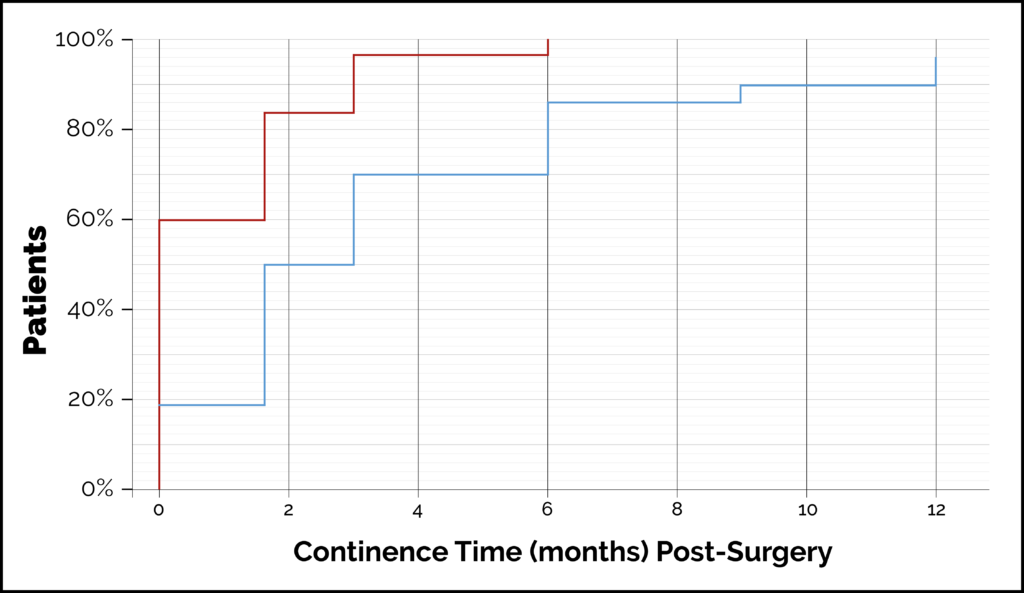

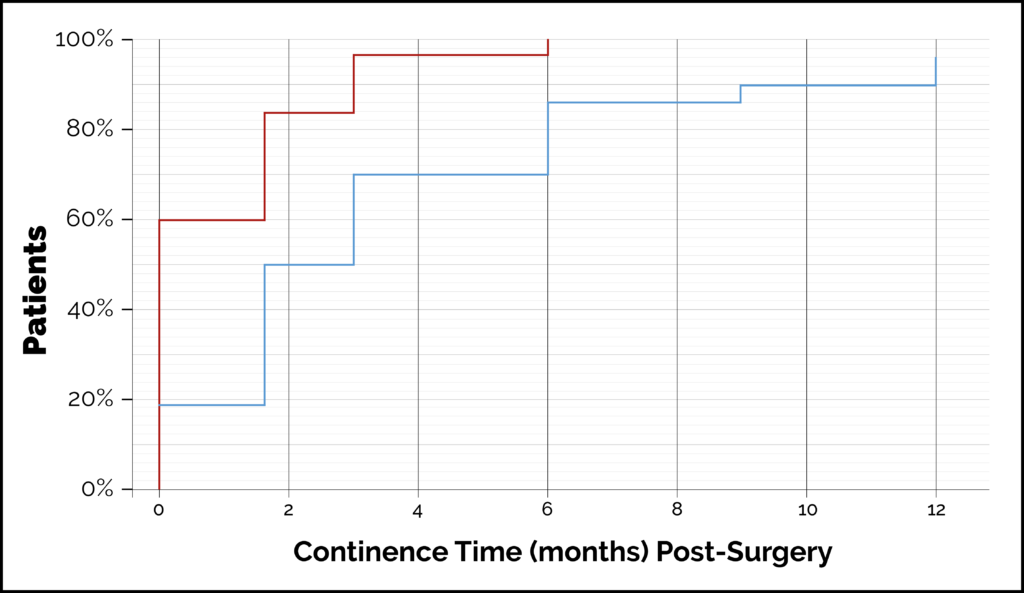

Prostate surgery can be approached in different ways in terms of the way anatomical access is gained to the pelvis. We have looked to see if different operative techniques influence urinary functional outcomes.Anterior Retzius Sparing

These surgical variations aim to minimally interfere with the muscles and structures related to continence. Using this approach, more patients are dry immediately after catheter removal and others become pad-free sooner than when the standard surgical approach is used.- 60% are pad-free immediately.

- 99% by six months.

- Less than 1% have a terrible urinary outcome.

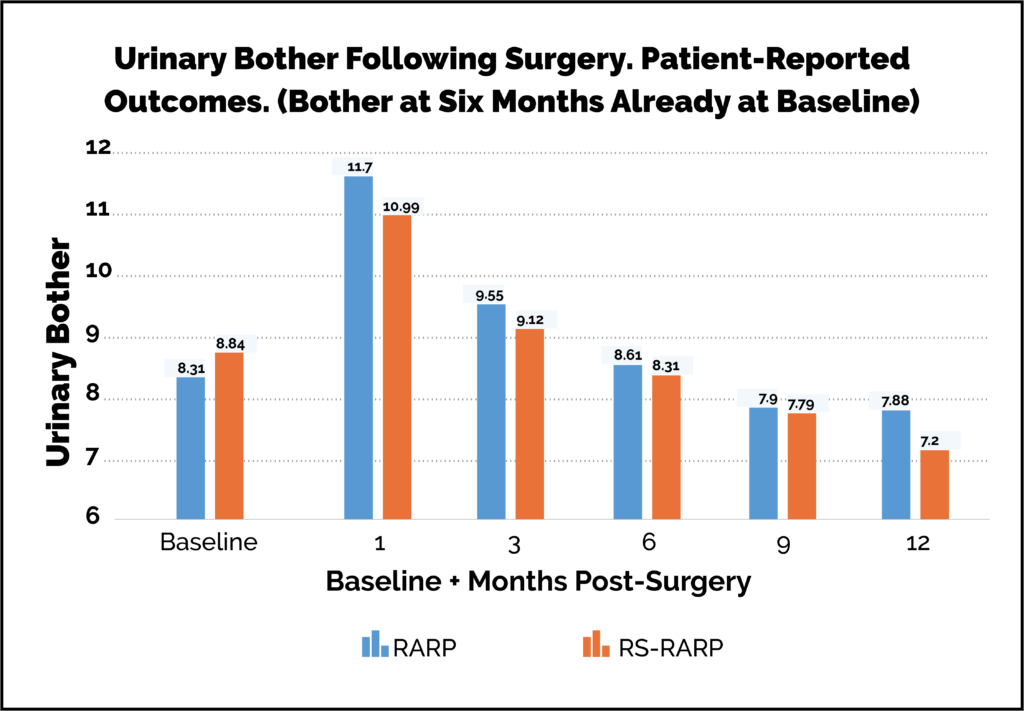

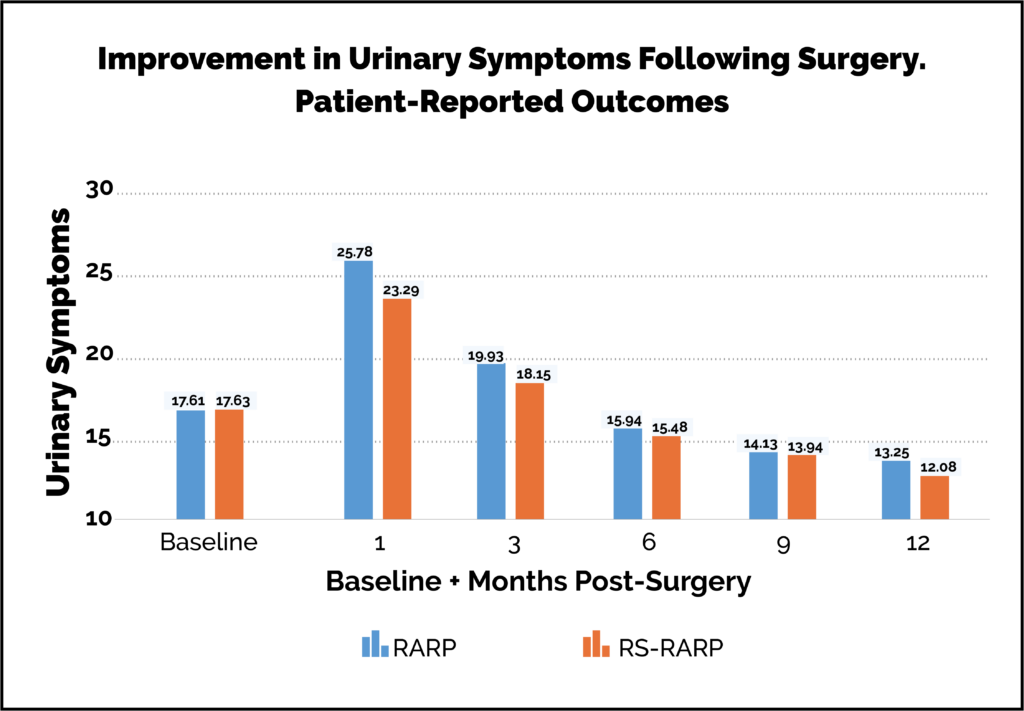

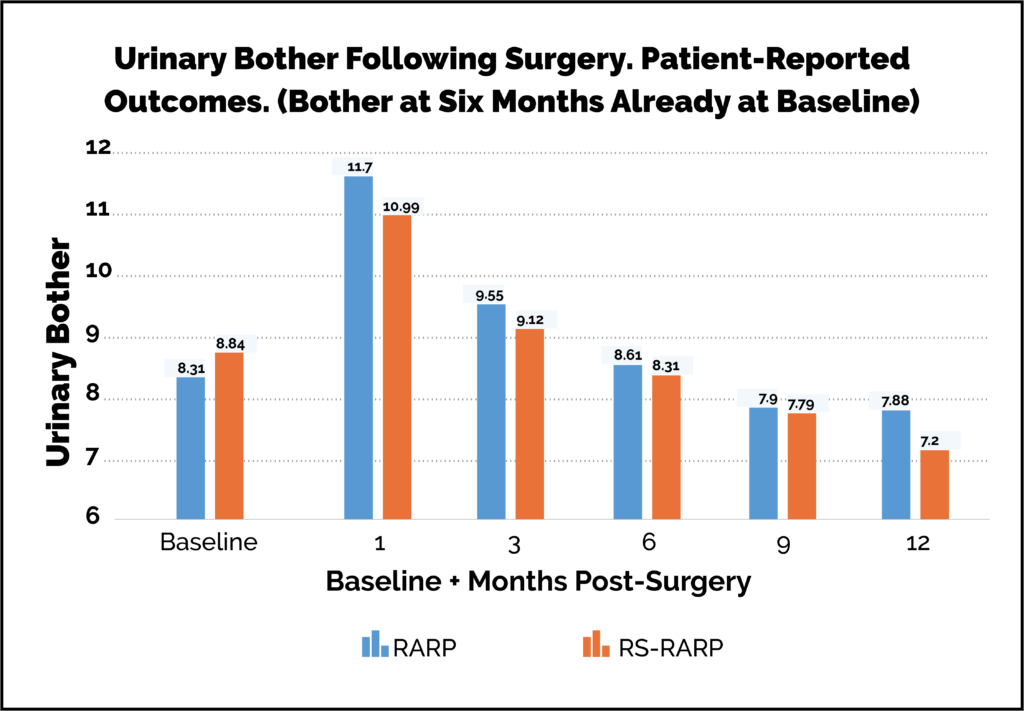

Retzius-Sparing Versus Standard Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy:

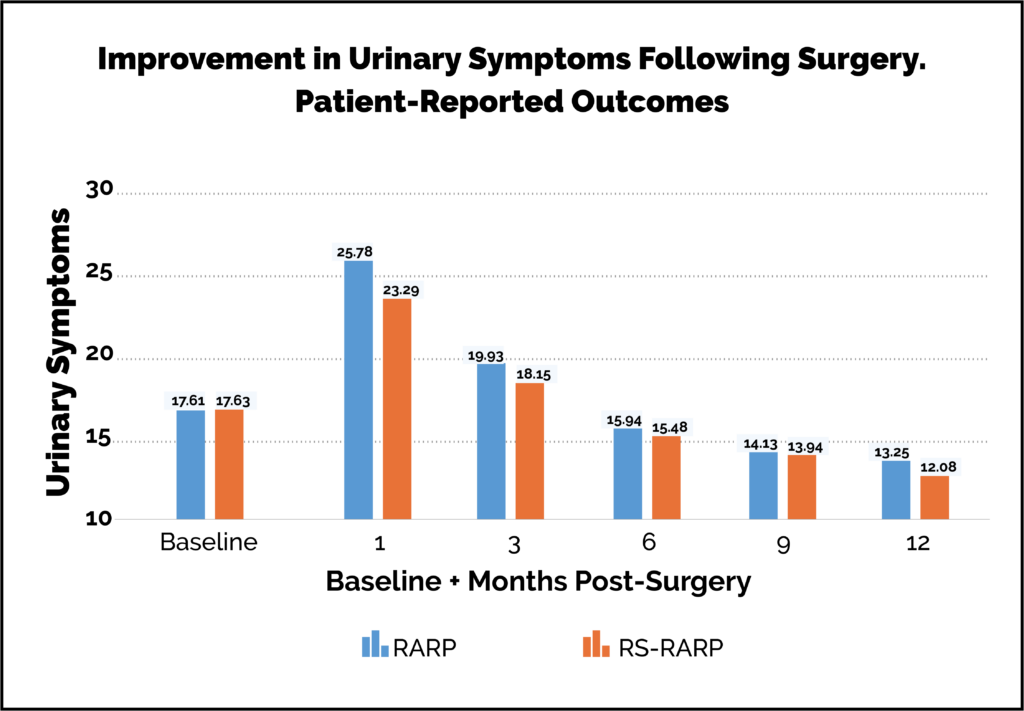

A Comparative Prospective Study of Nearly 500 Patients

Umari P, Eden C, Cahill D, Sooriakumaran P Oct 2020 J Urol Patient-reported outcome questionnaires are the best, bias-free way of assessing outcomes. With my colleagues Mr Sooriakumaran and Mr Eden, we have shown that urinary symptom profiles can be better following radical prostatectomy than they were pre-operatively. This is because we manage the age-related urinary obstruction caused by the prostate as well as the cancer. These graphs below show urinary symptoms and bother scores. They have been assessed by patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). This is regarded as the best standard for assessing patient outcomes.

Patients are often concerned about the effect of surgery on their ability to get an erection.

Patients are individuals and approach this issue in the context of their own perspective.

Of note:

- Some men are already struggling with impotence.

- Some men/couples are not sexually active.

- For some, risk to sexual function is a negotiable cost of seeking a cure.

- For some, the risk to sexual function significantly influences their choice of treatment.

- For some, sexual function outcome is their most important parameter.

The Operation

In order for an erection to occur, nerves need to be functioning to send the required signals to the penis. There are two erection nerve groups that run closely by the prostate gland on either side. During a RARP it may or may not be possible to keep the nerve(s) intact. Sometimes the need to clear the area of cancer makes their removal mandatory. Sometimes it’s just not technically possible to save them. Generally, if we intend to save nerves we do. Saving one side may be enough to maintain erections but saving both is better. 35% of men have both nerves spared. 70% have some sort of nerve spare allowed by the cancer. It may be possible to use ‘NeuroSafe’ as a way to see if it is reasonable to try to spare the nerves when there is some doubt about the safety of this in terms of clearing the cancer. ‘Neurosafe’ is a technique where pathologists can examine the tissue during the operation to check what is feasible whilst it is still possible to attempt this.Surgery and Erectile Function

- For some men undergoing a RARP, excision of the cancer has to include excision of the erection nerves and blood vessels (that lie close to the prostate gland) as they are thought to be invaded by cancer. The means of cure necessitates causing erectile dysfunction.

- If a man has pre-existing issues with erectile function before surgery, it is very likely to be worse after surgery.

- Men with pre-existing problems (eg diabetes and cardiovascular disease) that are known to be linked to erectile difficulty are more likely to have problems with erections after surgery even if they have acceptable erectile function pre-surgery.

- 65% of men presenting with prostate cancer have one or more pre-existing conditions such as hypertension or diabetes.

- A small number of men have very significant medical issues and that puts them at great risk of erectile dysfunction. However, surgery is still the best option for them because their cancer is horrid.

- Men with good erections before surgery and early disease are likely to recover erections that are good enough for sexual activity after surgery. To achieve this, it is common to need to use Viagra-type drugs initially.

- 80% of men under 60 years with good erectile function, no medical issues and both nerves spared do well with erection recovery.

- Men should be aware that post-surgery sexual function is different as there will be no ejaculation.

- Sexual activity can, of course, occur without penetration so there are options whatever the functional outcome.

- If penetration or erections fail following surgery, there are very successful options of interventions that may help function return. It all depends on the individual, couple acceptance and enthusiasm.

- It is worth remembering that sexual function declines with age whatever we do.

- Depending on the extent of your prostate cancer, other treatment options such as focal therapy and brachytherapy may have advantages over surgery in terms of preserving good erectile function if that is a key consideration for you.

- In general, if your erections aren’t perfect all treatment options are likely to adversely impact this. My advice would be that you should not use likely erectile function impact as a primary guide to treatment choice.

In Summary

Treatment choices and possible impact on erectile function are complex and specific to each person and their cancer. Support and advice is available both pre- and post-operatively to ensure the best possible outcomes for all patients.

There are recognised complications that can occur in prostate surgery because of the close relationship of the structures around the prostate. Understanding that they can be managed well can help reduce any patient anxiety.

During my career I have followed up my patients’ progress carefully. Documenting outcomes allows me to accurately understand performance and this allows me to target technical improvements and then assess those measures objectively. This means I can discuss with patients my own data outcomes and performance figures rather than quote what might be standard figures for this type of surgery. This facilitates meaningful patient consent for treatment.

Complications can arise in any surgery but my personal experience of more than 2000 cases of this type of surgery means that they are minimised.

The two most discussed complications of radical robotic prostatectomy are incontinence and erectile dysfunction and these are discussed in more depth elsewhere. There are other potential risks as outlined below.

1/50 patients stay an extra day in hospital for a minor problem.

Less than 1/500 experience a more significant issue (eg bowel injury).

Possible complications which you may wish to discuss with me in more detail are:

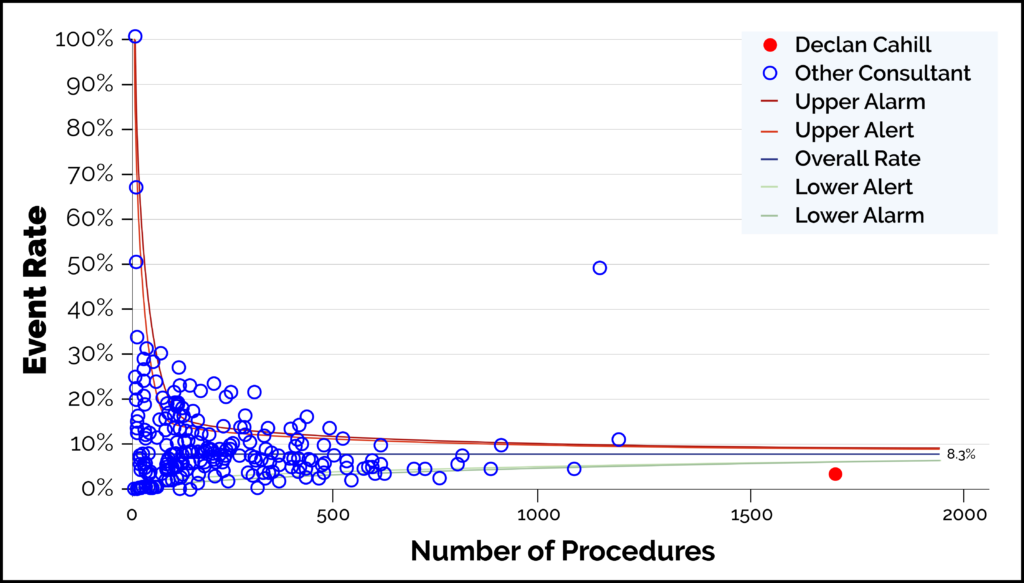

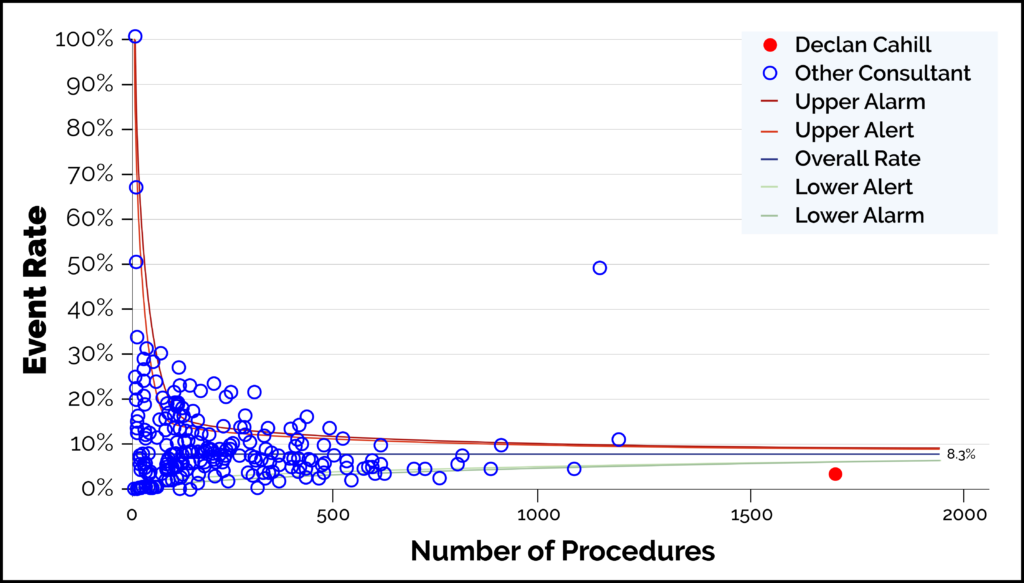

This graph demonstrates the number of cases and complication rates. Data on 1690 cases from the start of data collection by BAUS until closure of the audit on 31/12/2019. Declan Cahill is represented by the red dot and is the highest-volume surgeon. Complications 3.6% (listed here)

This graph demonstrates the number of cases and complication rates. Data on 1690 cases from the start of data collection by BAUS until closure of the audit on 31/12/2019. Declan Cahill is represented by the red dot and is the highest-volume surgeon. Complications 3.6% (listed here)

- Constipation. This can occur post-operatively but mitigated for by early use of laxatives.

- Bleeding in the pelvis. This is seen in < 1/100 and usually settles with bed rest and monitoring. Pelvic haematoma/bleeding requiring blood transfusion (this is a clot of blood within the pelvis). It resolves spontaneously but if it occurs the catheter needs to remain for four weeks instead of the normal one week. This occurs in 1/200 cases. Bleeding requiring return to theatre 1/1000.

- Wound infection 1/100 requiring antibiotics.

- Urinary infection while catheter in or after its removal.

- Bowel injury requiring a further operation 1/1000. May require a temporary stoma.

- Hernia requiring surgery at a later point. Groin or wound hernia 1/100. Needs surgery usually.

- Narrowing from scarring at the join between bladder and urethra (the passage from the bladder out of the body) 1/100. This is managed by one or more dilatations.

- Nerve compression at the elbow or wrist. This is rare.

- Lymph leak. This is again rare. This is related to a lymph node dissection during surgery.

- Post-operative thrombosis is rare. A deep vein thrombosis (a blood clot in leg) is very rare and a pulmonary embolus (a clot in the lung) is also rare.

- Scrotal swelling. This is uncommon but self limiting.

- Urethral stricture. Scarring in the penis tube. Again, this is rare and can be managed.

- Ileus. This means the bowel’s ability to actively work is reduced resulting in difficulty passing wind or stool whilst still in hospital. It settles with conservative rest. Less than 1/100.

- Neck and shoulder pain. This can arise from technical aspects of the surgery and can be uncomfortable but it is short-lived.

This graph demonstrates the number of cases and complication rates. Data on 1690 cases from the start of data collection by BAUS until closure of the audit on 31/12/2019. Declan Cahill is represented by the red dot and is the highest-volume surgeon. Complications 3.6% (listed here)

This graph demonstrates the number of cases and complication rates. Data on 1690 cases from the start of data collection by BAUS until closure of the audit on 31/12/2019. Declan Cahill is represented by the red dot and is the highest-volume surgeon. Complications 3.6% (listed here)

The Royal Marsden has produced some helpful videos for patients considering or about to undergo a RARP. See below or click here to access videos on pre-operative preparation, the surgery itself and rehabilitation. There is a video of a patient discussing some FAQs with Declan Cahill.

To see a video showing the typical experience of a patient on the day of surgery, please click here.